Burial's last interview

A little exclusive, because why not

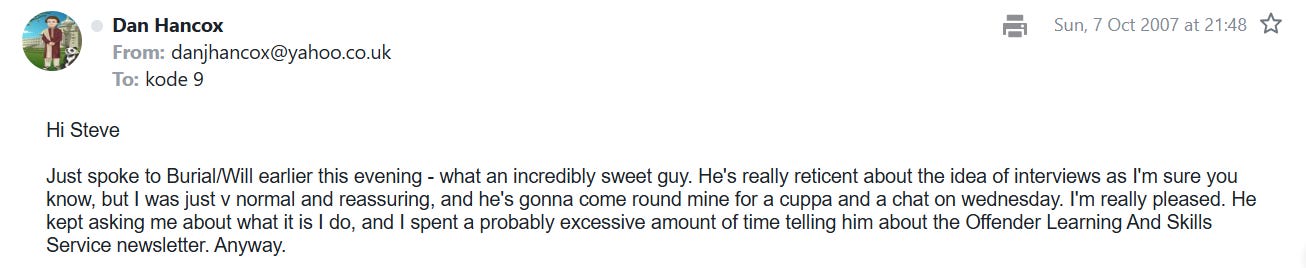

In October 2007, after some gentle lobbying of Hyperdub boss Steve Goodman (Kode9), I had the incredible privilege of interviewing Burial. Back then, after his mesmerising first two EPs and self-titled debut album, his identity was known by just a handful of people. “Only five people know I make tunes,” was the quote the Guardian picked for the headline of the piece I subsequently wrote, published just before his second album was released in November. Untrue was hailed as an instant classic, and suddenly Burial was no longer the dubstep scene’s worst-kept secret.

Setting up the interview required a little more gentle persuasion, and a bit of Cold-War-Vienna-like mystique. I got a call from an unrecognised number saying hi, this is Will. We arranged to meet at Balham station in south London, and — because I had no idea what he looked like, because nobody did — I volunteered to wear a bright red jacket for identification purposes. He was a bit late, and I spent some time scanning the streets I had grown up in, guessing in vain who the man behind the mask might be. He showed up and apologised very sweetly, and we walked to my flat in Tooting to do the interview… except, not an interview: he was unsure about doing press — and as we’ll see in a moment, entirely justified in this scepticism. But nor was he reserved, once we got talking; he speaks with a passion and intensity like few people I have ever met, let alone interviewed. But he was wary of exposure — of emerging into the light, when, and this is totally fair enough, all he ever wanted was to lurk in the shadows at the back of the club, and make tunes in his bedroom while everyone else was asleep.

And so we agreed to re-code what we were about to do “just a casual chat about tunes”, in Burial’s words. We sat on my sofa and had two cups of tea each, and he settled in. After about an hour, he let me turn on the dictaphone that had been sitting on the table. I remember saying, half-joking “look, I’ll turn it over so you can’t see the red light — pretend it’s not there” — and we kept talking.

It would be Burial’s last interview.

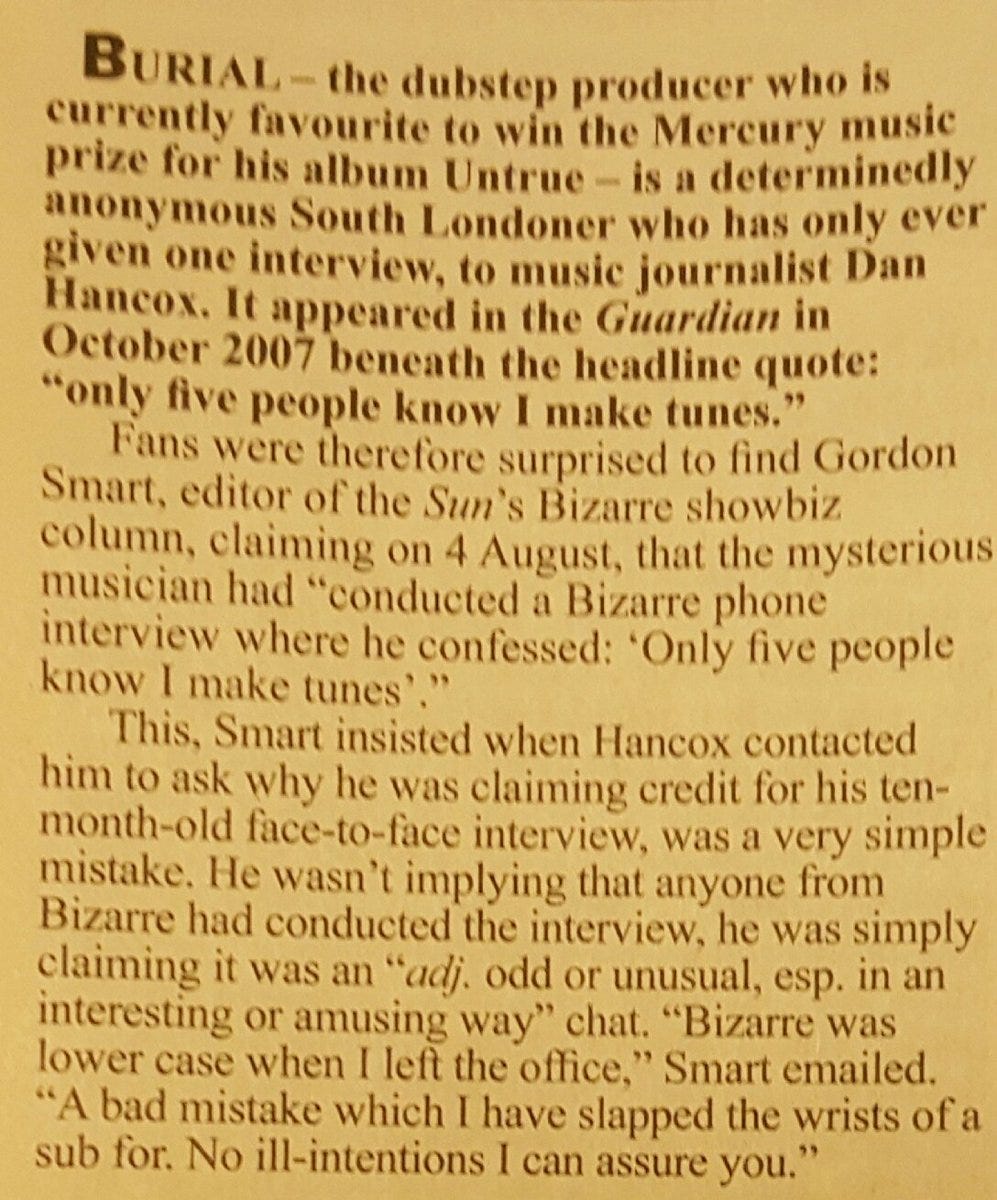

The following year, in July 2008, the Mercury Prize nominations — more like Mercurial Prize, because they change the criteria every year, rightguys — were announced, and Burial was soon the bookies’ favourite. The Guardian illustrated the shortlist announcement with Burial’s pencil self-portrait from the cover of Untrue, rather than an actual photograph of one of the other artists. The Sun’s unfortunately named Gordon Smart, in charge of their ‘Bizarre’ showbiz gossip column, was outraged that an anonymous artist might win such a prestigious prize, and launched a tedious campaign to unmask him. This unwanted attention in turn led the users of dubstepforum.com to mount a misinformation campaign to throw the Sun off the scent — pleasingly, the suggestion that Burial was in fact an alter-ego of Fatboy Slim made it into print. Eventually, Smart plagiarised my Guardian piece, tried to pass off the quote from the headline as his own, and then lied about it when I called him out on it. The events were commemorated in Private Eye:

Kode9, meanwhile, commemorated the events by making the furious, brilliant Black Sun — his riposte to Smart. And because Burial wouldn’t perform at the Mercury Prize ceremony (obviously), and Hyperdub didn’t send anyone, Elbow won instead. Burial was forced by all this bullshit to post his actual name on his MySpace profile — Will Bevan; although really, a thread running throughout this post is that that information is not of interest to you — and a photograph of his normal adult face. It sucked at the time, but it worked: everyone stopped bothering him, and he has quietly gone on to make 18 more years’ worth of incredible music — music that er, I am not going to get into right now. We’d be here all day.

I was prodded by a friend recently to look up the 2007 interview transcript, apropos of nothing much. And thank god I still had it lurking on an external harddrive, because what he said that afternoon was, as I remembered, endlessly captivating. The whole Guardian piece was only 1200 words — this transcript is 3000; there’s a lot of gold here that has never seen the light of day. There is candour, self-effacement, a righteous and often funny spikiness about bad music, and plenty of urban romanticism. (And yes, there are nightbuses, whalesong and McDonalds.)

As he does in his tunes, in conversation Burial would take an idea and dreamily pursue it into the mist, chasing it, refining or iterating his approach, earnestly trying to capture something apparently ineffable. Burial can do that rare and beautiful thing of exploring his passions and his processes in a way that makes his music sound even richer. I take no credit for this, I did nothing but make lots of tea, sit back and let him talk — but I do feel lucky to have captured him doing it. There are three or four other interviews out there (Private Eye were in error above, when they wrote it was his only one), from before mine: Mark Fisher’s and Martin Clark’s spring immediately to mind. This is just the last one… and who knows, maybe not the final one. It’s up to him.

There’s no special reason for sharing the transcript now — I momentarily thought about waiting for the 20th anniversary of Untrue in two years, but honestly I hate that way of thinking. Life’s short, enjoy Burial’s words — and his music — now.

I’m not going to paywall this, but honestly I think it would be best for both of us if you subscribed. And I will casually mention that my latest book, Multitudes: How Crowds Made the Modern World, is out in hardback now, and out in paperback 4 November. Buy it here.

And if you stumbled on this post because you googled “burial untrue steal metal gear solid shell casing drum sound a level music coursework”, you may also enjoy my book about grime and London, Inner City Pressure — aptly, it came out one month after Burial’s remix of the Goldie classic Inner City Life, from whence I took the name.

Right then.

Burial’s last interview. 10 October 2007, Tooting.

Have you heard your tunes played in a club?

Once or twice. My tunes are really quiet. I always feel really defensive of them, like it’s their first day at school, and they’re going to get bullied.

Your tunes aren’t really club tunes are they?

No, they’re more influenced by when you come back from being out somewhere… in a minicab or a nightbus, or walking home across London late at night, and you’ve still got the music kind of echoing in you.

I hate that idea of coffee table music though, it’s just for wankers. It’s not necessarily a bad thing if music’s sometimes just in the background. Club music’s different, it has to have a movement, that’s why in a club you can have a sudden shift in the music, a new noise will come in, and the whole place kicks off from some tiny thing. I quite like it when you listen to music in your headphones, and you’ve got real life going on around you.

It’s pretty sad, but my music probably is just for moody people to walk across London in the rain to. That might sound rubbish, but most of my experience in life has been exactly that. Everyone knows that feeling, everyone. And if they don’t, they probably spend too much time in All Bar One. My music’s like a little sanctuary, it’s that 24-hour stand in the park serving tea and coffee, a light in the darkness.

I blink and years seem to go past. When people talk about music in this country, its recent history, there are always certain things that get ignored, and one of them is how important hardcore rave music, jungle and garage were.

The original ravers, maybe they’ve stopped going out now, and got on with their lives, got on with families and work, but the afterglow of the music’s still in them. Or maybe there are people they used to go out with who are no longer with us, and it’s heavy. It’s been around long enough that a single sound, even a single synth stab, or a single sub-bass sound, could kill someone, because of that memory, because they know what it means.

This music has been around long enough that it can have that effect on people. I think it’s actually a part of what England is now. People lived and died for that music. It’s not just a badge you wear because you’ve been to a club a few times; it means everything. And I think dubstep’s the latest stage in that progression.

One of the things about living in London is that you live through the experiences that other people have had, and the stories people tell you. I’m not old enough to have been to a proper rave in a warehouse, but I used to hear these stories about the late 80s and early 90s, about driving off into the darkness to the outskirts of London. It really caught my imagination.

But there was also a sense of ending and sadness that it had died, because club culture got commercialised in the late 1990s, it got taken off ravers and sold back to them. The truth is my tunes were never designed to be heard by anyone. I made them for my brothers — for my older brother, because he was around then and used to go to those raves, and used to make tunes when he was young. I wanted to recapture that lost sound for him.

But it’s still out there. There’s a signal, or a light. It’s like there’s one person holding a lighter in a warehouse somewhere. I think about it like that, I’m romantic as fuck about it. I don’t like this idea that club music should be a disposable thing, that’s bullshit.

That’s why I love dubstep, because it’s got that spirit. I don’t see it as independent genres, dubstep, jungle, hardcore — I see it as all one thing.

It’s the English rave spirit

Exactly. It makes so much sense to me that all this stuff was suburban, halfway between the city and the forest… that’s so English. It’s like English mysticism. It’s like the Black Lodge in Twin Peaks, it’s like the curtain between the wolves and the city. That’s why I love FWD>>, because of that curtain, separating the bar and the darkness of the dancefloor.

I’m only messing around, I don’t really know how to make songs properly. I feel like I’m cheating almost, because I’m releasing tunes, before I’ve really learned how to make them. I have the utmost respect for people who are properly technically gifted with their music, but I’m not that guy. I’m trying really hard to learn, trying to catch up.

Wouldn’t you be worried about lose that ineffable quality if you became a fully proficient technical whizz?

Yeah well that’s the problem, you do often lose that quality when you spend too long on a piece of music. I’ve been trying to make my music for two years in my head, but when I look back at it, I actually made the whole thing in the space of a week, albeit spread out a bit over that time.

It’s almost like I’m trying to make that imperfect record, before I learn how to go away and do it properly, I want to make these more DIY tracks. There are certain tunes on there that are so obviously not that sophisticated… I’m just pretty defensive about it, because I was never really expecting so many people to hear my record.

So how does it feel that people did?

I was buzzing, absolutely buzzing. But I also had to hide that feeling, because no-one I know really knows I make tunes. I couldn’t be at my job and just tell everyone, so I was absolutely buzzing, but I didn’t have anyone to tell… but I could tell my brothers, and that was all that mattered.

Before I make another dark album, I want to make an album full of singing, not just any old singing, but the singing I love: the girl-next-door singing. It may seem odd that I made an album that fast, that’s full of pitched-up vocals, the kind that sound like a chipmunk singing in the shower, but I can’t help it. If really technically-minded people who just want a big bassline don’t like it, then too bad.

I made it so quickly. I realised just the other day that every tune on my new album has the same drum sound — it’s just the sound of my brother’s lighter. It may not sound the same on every track, but it is. And the other noise I repeat loads is from some budget Vin Diesel film, where he gets keys out of his pocket or something, and it’s just this jangle noise, but I immediately thought “I fucking love that sound!”. I just cane it, I use it way too much.

I just love rain. I’d do anything to be out in it, to be on the edge of it, or high up, looking at it. There are a lot of shit tunes that I love because they have the sound of rain or thunder in them. It’s that simple, it’s nothing complicated (laughs).

I love that feeling, when something’s really getting at you, and you go out and walk in the rain, and you’re freezing, and a shiver goes up your back, in an attempt to warm you — to look after you. I think everyone knows what that feeling is like.

I can’t deal with really sophisticated glitchy things, but I used to love it on drum ‘n’ bass records when you’d get the big drop, when the drums leave it, and there’s just this sound echoing out there. And you hear that in a club — or even on headphones, because in your head it’s not that different from being in a dark club. And there’s that little bit of noise on the record, or on the tape.

Everyone goes on about vinyl crackle, but I love tape crackle, that’s a beautiful sound. I just like tunes to be as atmospheric as fuck, I don’t like that clean sound. I don’t see the point of that clean sound, it’s so neutral.

The other day there was some kid on the common who looked like he was in the army or something, and was practising those weird little trumpet noises, trying to get one of those refrains right, just playing the same short sound over and over again. And it was almost like when you hear thunder. It’s that shiver, you just go into a siege mentality when you hear thunder. It’s almost like you’re at war and hear the guns, you’ve got that atmospheric awareness that comes from hearing a sound that powerful, but that distant. Like hearing whale-song — people diss the fact that I love whale-song, but the truth is I do (laughs). It’s that weird cry, that far cry, it’s a really beautiful idea.

Do you like to make music with the TV on?

Sometimes I can’t help it, because people might be watching the TV. But I don’t mind it. I don’t want to make my tunes in a studio that looks like a spaceship. I do really admire people who are into that stuff, but I’ve got a really rubbish computer, I can’t even move it, so I haven’t got much choice.

I made a lot of tunes for the second album that were really detailed, darkside, really moody — that maybe fitted in with what people thought my next LP was going to sound like, and then I just thought… it sounds weird but I… I don’t find it easy making tunes.

Things have been difficult for me recently. And then finally I had this mad time of real life being on my case. You don’t want to be just… bleak. Making quite a happy album, really fast, was what I wanted to do, and I needed to do it. And now I’ve done it, and it’s imperfect, but I’ve done it.

The reason I’m proud of it is not because it was the result of a thousand decisions that went exactly how I wanted them to, made in a studio where musically it’s all… [tails off] …it’s not that at all. You make the tune and you’re in a certain mood. You choose a certain vocal and let it circle around, and even if that tune’s a little bit dry, it can end up meaning a lot to you. And in the end I’ve made a whole album of just those tunes.

(laughs) I’ll do the high-tech fucking super darkside album next.

So was this album made late at night as well?

Yeah I would literally sit around waiting for night to fall. I don’t want to be a wall-starer, y’know staring at walls, but I would be waiting for night-time, thinking ‘I really want to make some good tunes tonight’. Or I would go out walking, wait for it to get dark, and then I’d go back… I love that feeling when you know that almost everyone in the city is asleep. That’s got to be the only time to work. I get up really early sometimes, or I’m awake all night, and you see the people and the city waking up around you… I actually feel a little bit angry at people (laughs), like they’re intruding on my silent world.

Or you know when you’re coming back from somewhere on the tube, and everyone going to work is coming the other way. Like you’re on a platform and you’re the only one who gets that train. Or you’re on a train with all the people going to work, and you just get this wrong feeling, like you’ve just escaped from somewhere.

I’ve walked back from The End late at night, all the way across London, and it was getting light … it’s just a funny thing, but it’s a little bit wrong.

When you’re making tunes you think you’re making a certain style of music — you’re reaching for an ideal of all that music you love — but you’re not. And then hopefully you get lost, and head off the path into the dark.

Club music always has trouble doing albums, but I’m obsessed with the idea of making albums.

[There follows an aside where Burial, laughing, endorses the McDonalds ‘I’m Loving It’ slogan: “the thing is, I actually do love it. I’m in nothing but agreement with it… ‘finally a slogan that expresses how I feel about McDonalds!’”. I can also recall from these conversations — and reveal for the first time — that the artist was a fan of the under-appreciated and long-since vanished baked potato chain Jackets. Another haunting presence on the streets of south London.]

Was there a point where you decided ‘I’m going to be anonymous, I’m just going to be ‘Burial’?

At first I was sending Steve tunes, and I didn’t have a name. And ‘Burial’ was just the name of one of the tunes, and Steve said “oh is that your name?” so I said “no… err, yeah, alright”.

I want to make music that you can get lost in. My favourite tunes are white labels, where I’ve got no idea who made them. I used to love that about old jungle tunes, when you didn’t know anything about them, and nothing was getting in the way of you enjoying it. I remember times when I’d hear a garage tune on pirate radio, and would be sitting there waiting for the DJ to say what the record was afterwards, but they’d be so deep in the mix they’d just keep going, and I’d be sitting there for an hour hoping to find out what the tune was called.

And then in the end I realised that I liked it better that way. I liked the mystery. And I realised how amazing it would be if I could capture that in my tunes. Also it’s fun, because I’m basically like a really rubbish super-hero… only about five people outside of my family know I make tunes, I think. I hope. And it’s going to stay that way.

So as well as the fact that your real identity is concealed from the public, is it also the case that people in your real life don’t know that you make music?

Yeah, and I like it that way. But… I’ve had times when I’ve had mates sitting next to me and they’ve put my tunes on.

And you didn’t say anything?!

No. I was just sitting there whispering to myself ‘please don’t put that on — or at least, don’t say anything bad about it’ (laughs). I’ve had mates turn to me and say ‘oh yeah, Burial’s a girl, I know someone who met her’.

And you’ve you resisted the temptation to say ‘that’s me’?

It’s not fakery, it’s just the way I am. I couldn’t do the other stuff if I tried. If I go out I just want to be in the dark, at the back. I’d love to do some collaborations with other producers. I wanna go out there a little bit, but keep a tight rein on it. I don’t read press, I don’t go on the internet. It’s more fun. Keep it locked away. The lost art of keeping a secret… I want to do it properly. And that’s the thing, once you’ve got it, it’s got to be 100% or nothing. You can’t be half-anonymous.

Do you ever use recording studios?

I’ve been in a studio four times. For the next one, I really want it to sound deadly. No vocals, no crackle, just ‘dark it up’ some. I’m just interested in that idea of militantly darkside 2step drums. But there are loads of different directions I could go in. I could pick any one of my tunes and make a whole album based on that sound. There was a tune on the first record called Distant Lights, and Untrue is just getting that tune and diving through it — I’ve made a whole record of tunes like that basically.

There are some tunes on there that people could hear and think ‘oh I’m just going to do a technically better version of that kind of music,’ and I’m a bit defensive about it. I’m defensive of 2-step generally, of UK garage. For a while people have been talking about it like it’s dead, just cause it’s not written about in magazines or whatever. But real people still listen to these tunes. There are loads of fantastic garage stations still about, and you’d think they’d never existed.

I’m as much a fan of that stuff as I am of dubstep or jungle or drum ‘n’ bass. I’m glad it hasn’t become ‘internet music’. I don’t really want to talk about the internet, but… I’m actually a bit disappointed in how things I love, like drum ‘n’ bass, became… global. I know that sounds a bit wrong, but it’s true. It forgot where it was from, and made such a rush into the internet that it became internet music.

That sounds like hell to me. It just loses all its edge, it’s no longer dangerous, no longer underground; it just becomes this sort of one-note-producer internet music. I would die before I’d ever sit down and listen to that stuff. It’s this kind of neutral, try-hard, blokey music — it was never about that. A lot of even the darkest old drum ‘n’ bass tunes still had singing in them. People still used to play them in their cars. It wasn’t just a ‘let’s try and look rude and nod our heads’ thing.

What about this macho-sounding trend in dubstep?

Yeah fuck that.

What’s the worst vibe you can get in a club? It’s when you get a bunch of people who’ve come into a club and they’re looking around like ‘oh so this is what dubstep sounds like…’ Fill a room with those kind of people and you’ve got the worst atmosphere possible in a club ever.

And the thing is, some of that macho attitude starts to creep into the music, I see it as the same thing — and those macho tunes, they’re not even properly dark, they’re not properly fierce. One single Dillinja kick-drum would destroy those tunes.

Dubstep will be fucked if it goes down that macho route, and it’s already started to happen, these same people are now making dubstep instead of drum ‘n’ bass.

I love garage because it’s the exact opposite of this ‘clang’ music. I love that skippy rhythm, listening to it in the car, driving through the night. I love how garage is up, and sugary. It was this beautiful thing — but people didn’t notice how beautiful it was at the time.

What a read tbh, shows how precious everything was/is for him. The culture, making it for himself and his brothers, the decision to stay anonymous, and his relation to the rain and dark nights. Shows the level of authenticity and alignment he has with his work. Almost as if his work tells us who Burial is. Thank you for this.

Can't believe how humble he was, and surely still is, for a guy who has essentially moulded UK dance music beyond what anyone thought it was capable of.

Also had no idea Black Sun's name was because of that notso Smart fella - anywhere I can read about this?

Cheers for the great piece