“We run the streets today!” is a line that still rattles around my head on a regular basis. I think I’m remembering it being yelled by a 6th form student protester, marching down the middle of the road in Whitehall in November 2010. This was the fractious beginning to the deep, painful assault of Tory-Lib Dem austerity, when London in particular and England in general experienced the biggest student protests in their history, and then the biggest riots in their history, all in the space of 9 months.

Ironically, given the idiom, there is something thrilling and transgressive about being in the middle of the road. By which I mean: there is something thrilling about it when you’re not in a vehicle. When I was in my late teens, and coming back from a club in Brixton at 4am in the summer, I would turn off the high street and into the becalmed residential backstreets of Balham, and for the final stretch of my walk home, stride happily down the middle of the deserted streets. I remember being surprised at how empowering it was — an act of defiance that no-one was watching, no-one was affected by, and no-one cared about.

With this in mind, you could probably guess that I loved every minute of my first Critical Mass bike ride — the 30th anniversary ride through central London, on a beautiful, springy Sunday afternoon earlier this month. The clue is in the name: with enough people gathered together at once, cyclists of all shapes and sizes (plus rollerskaters, skateboarders et al) can form a two-wheeled carnival-caravan, and temporarily reclaim the streets in their entirety, rather than being squashed unhappily into the curb.

Critical Mass began in Seattle in 1992, and its first ever outing in London was two years later, in April 1994. Since then, come rain, shine or hail, this leaderless, two-wheeled revolution meets on the South Bank once a month, and for a few hours proceeds to take back central London from the toxic fumes and humvee-like armour of the modern car. Only 30-40% of households in most inner London boroughs have access to a car: it is a minority pursuit belonging to the most wealthy, poisoning the majority. Even after long-overdue improvements to better protect pedestrians and cyclists in the last decade, 102 Londoners were killed and 3,859 more were seriously injured in road traffic accidents in 2022 — 80% of the dead were walking, cycling or motorcycling.

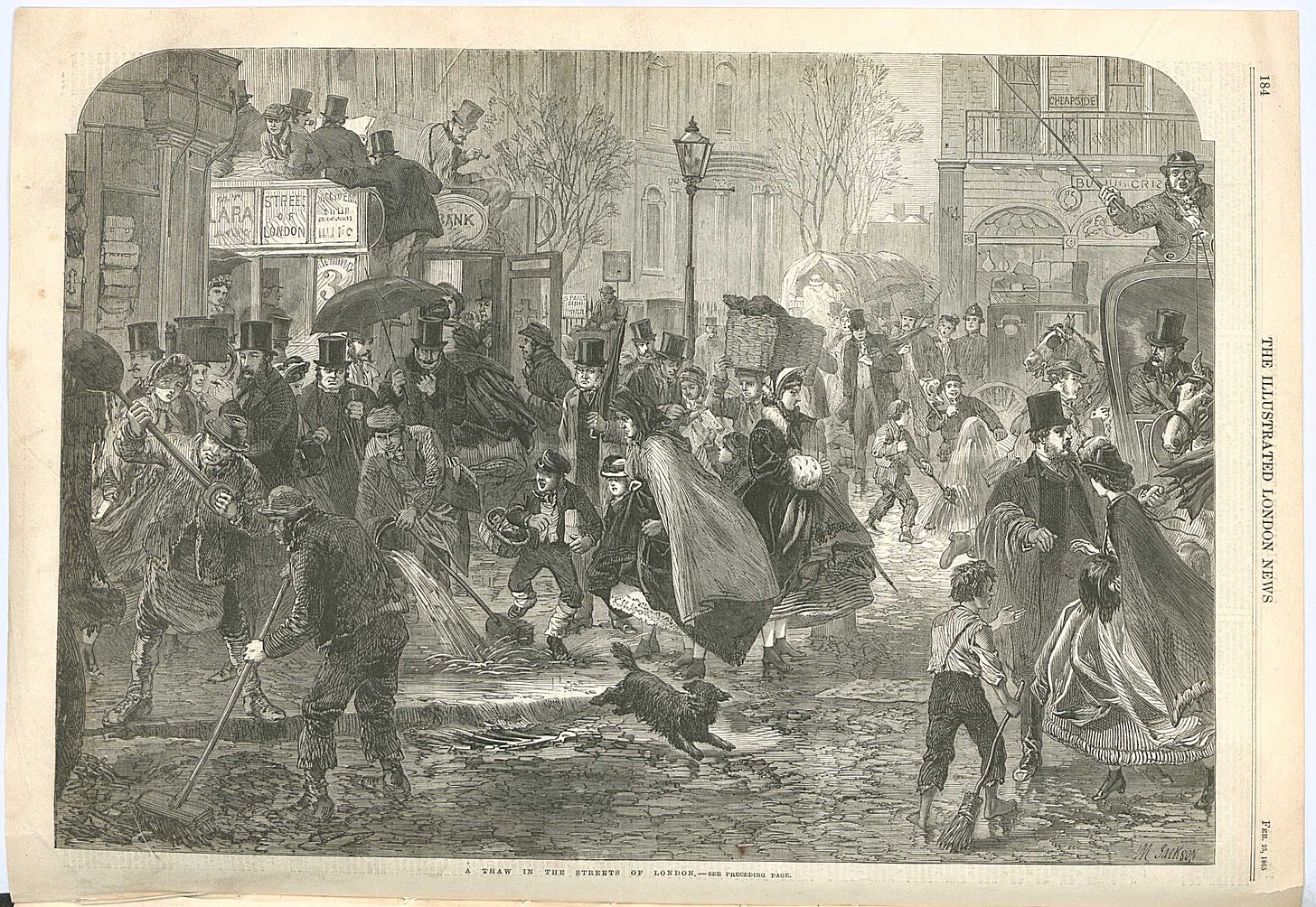

In the ‘urban crowds’ chapter of my forthcoming book, Multitudes: How Crowds Made the Modern World (published by Verso, 22 October 2024), I argue that the motor car is emblematic of the privatisation of city life in the last century: the enemy of urban conviviality; an ugly, fortified bulwark against spontaneous and joyful encounters with strangers. And while I’m obviously not about to advocate for a RETVRN-style regeneration of Victorian London, it’s simply a fact that our city streets used to be considerably more shared, more public spaces — and it’s simply my opinion that they should be again. Just without the cholera, workhouses and silly hats; perhaps a bit more like Ada Colau’s Barcelona, with its wonderful Obrim Carrers (Open Streets) and Superblocks iniatives (there is more on this in Multitudes too).

Suburban Tories and the far-right like to get worked up about The War On Cars, because they believe that true English sovereignty and freedom can only be found by sitting alone in a traffic jam, fumingly silently and listening to TalkSport. The truth is the last century has seen the car industry, its lobbyists and their friends in parliament wage war on us, the majority of citizens. So I say bring it on: let’s have a war on cars, but for real this time — we’ve been far too accommodating up to this point. Unless you have mobility issues, there is simply no need to run a private car in a densely populated city like London with a vast, heavily subsidised public transport network.

Ride Wid Us

And what a giddy, joyful glimpse of a better world Critical Mass provided. There were riders aged 7-70; teenage boys and girls doing wheelies, hippies, crusties, anarcho-punks, Deliveroo riders in uniform, mum-and-daughter duos, sensible bike dads with trouser clips, people in sun-hats, helmets, three-piece suits, summer dresses, basketball jerseys, and a Spanish Second Republic-themed lyrca outfit. There were riders with keffiyehs, Palestine flags, rainbow flags, several people in Brixton Cycles’ Jamaican tricolour kit, and a group of Black British cyclists in ‘Routes and Culture’ tees. There were riders with their dogs in a basket, and even one with a cat in a basket; people brought their children, some of whom rode their own diddy little bikes, while another happily sat drawing with crayons from the comfort of a cargo-container. There were bike-mounted soundsystems playing drum ‘n’ bass, more drum ‘n’ bass, and for one sweet moment, ‘Did You See?’ by J-Hus — before reverting to drum ‘n’ bass (the music policy is the only thing I would change a tiny bit). There were knackered old hybrids, high-end road bikes, ebikes, Lime bikes, Boris bikes, kids’ bikes, tandems, BMXes, hybrids, cargo bikes, penny farthings, and even a velomobile. I spoke to a woman my mum’s age in a yellow high-vis jacket who was, like me, on her first ever Critical Mass ride, beaming about what fun it all was, and then ran into my friend Ben, who had just taken part in his first ‘corking’, whereby riders at the front position their bikes at cross-streets and intersections to block off cars and keep the rest of the ride safe. “I’ve never felt so alive!” he laughed.

The thousand-strong crowd contained a true mixture of Londoners, spanning age, class, race and gender — the tired trope of the monied, macho, ‘all gear and no idea’ MAMIL is a miniscule fraction of the people who actually cycle in London; to work, for work, to school or college, for fun, for exercise, or simply because it is the only way they can afford to get around. And as varied as the crowd was, I was also delighted to be reminded that London still contains an anarch-ish counter-culture, at the core of Critical Mass, and they have survived in the city’s turbo-gentrified, post-squatting-ban, 2020s incarnation. I half-thought the anarchists had all been squeezed out. I will hopefully write more on the brilliant and Critical-Mass-adjacent group the Space Hijackers (RIP) at some point.

Three decades of reclaiming the streets

Thirty years of consistent monthly direct actions is an incredible record — perhaps unsurpassed in its consistency. Perhaps it is reflective of what is possible when you can find a way to make activism this purely enjoyable, while still making a very forceful and very public point. Putting your politics into practice rarely affords you such fun and conviviality — it rarely affords you so many opportunities to go ‘wheeeeeeeeee’. A Freedom News contributor summarised CM’s achivemement at making it this far:

“It has been through thick and thin, had its highs and lows, and been subject to harassment and surveillance, mass arrests and prosecutions, and legal attempts to shut it down. But still, it endures every month without fail, an unbroken line for three decades. It celebrates the diversity of cycling in this city to temporarily re-occupy our city streets, which have been nearly monopolised by hyper-capitalist car fetishism. It is a living, breathing example of an anti-authoritarian, non-hierarchical event that has seen so many other movements and organisations come and go.”

As the writer says, it has faced numerous challenges, beyond psychopathic drivers threatening riders with violence: something which, depressingly enough, I witnessed, even on what was — drum ‘n’ bass aside — a quiet Sunday afternoon in the city centre. One driver was so incensed at the prospect of an extremely minor delay to his journey he ended up standing alone outside his car, in the middle of Cambridge Heath Road, threatening people, smashing a glass bottle on the asphalt and screaming blue murder. The Critical Mass guidance is to not rise to this kind of bullshit, to simply smile and wave — with a soft answer, to turn away a whole flock of wrath. It is incredibly effective, and just leaves the fulminating drivers looking pathetic and red-faced.

Critical Mass has faced numerous overheated legal and policing obstacles over the years. “From the outset, the police tried to close it down,” Tom Williams, who has been coming since 1994, told me as we milled around on the South Bank before setting off. Police efforts to declare Critical Mass unlawful went as far as the High Court, the Court of Appeal and then even the House of Lords, during the 2000s, turning on the question of whether this was a ‘public procession’ that required advance notice of an exact route, to be cleared with the authorities. “Roads are public space!” Williams exclaimed to me, by way of a reminder of the fundamentals. “We have every bit as much right to be there as the cars do. We’re just not polluting the person behind us; we’re sucking up their fumes instead.”

Another veteran rider, Denzel, who has been riding with Critical Mass since 2005, wore a home-made yellow t-shirt with ‘CRITICAL MASS ARREST’ written on the back, referencing the outrageous protest ban enforced around the London 2012 Olympics. On the night of the opening ceremony, 182 cyclists (including a 13-year-old) were arrested merely for riding their bikes on London’s roads. “I was late, and as I arrived, I saw people were being kettled, so I thought okay, hometime,” Denzel recalled, as we paused on Mile End Road, waiting for the next junction to be made safe. “So I started cycling home. But I was pushed off my bike by the police, arrested, and handcuffed, face down on the ground, and put in a cell for 13 hours. And then I was banned from entering the borough of Newham, or going within 100 metres of an Olympic venue.” Many would later successfully sue the Met for wrongful arrest.

London transformed?

This is not the time or the place to do a comprehensive inventory of just how much has changed on London’s roads since 1994 — we would be here a while — but suffice it to say that the first time I owned a bike, when I was 13, pootling around the backstreets of Balham and Tooting to friends’ houses, it was just generally understood that you didn’t cycle anywhere near places like Elephant & Castle roundabout, terrifying, multi-lane vortexes of cars and heavy goods vehicles. Even attempting to navigate it would be dicing with death.

Tom Williams told me that when Critical Mass started in the 1990s, the London Cycling Campaign were losing one of their members every month — one human being per month being killed by vehicles on London’s roads. The consensus, chatting to riders like Tom who had come from outside the capital for the day to celebrate the anniversary, is that cycling pretty much anywhere else in the country is still every bit as dangerous, marginal and scary as it was in London in 1994.

London at least has transformed considerably in Critical Mass’s three decades; even, in fact, in the last few years. The capital’s Cycleway network has quadrupled in size since 2016 — from 56 miles in 2016, to 223 miles today. Daily cycle journeys are up 20% on pre-pandemic levels. I only bought my first adult bike in 2019, and I am lucky to have got back into it at just the point it was finally becoming safer, and easier to do so — the music industry acquaintance I knew in my early 20s who was left in a coma after being flattened by an articulated lorry didn’t exactly encourage me to start cycling again. And there is still a long way to go — some of these ‘bike lanes’ aren’t doing anything to make anyone safer: a white bike stencil painted on a narrow strip of asphalt in the gutter does not, unsurprisingly, constitute any kind of protection from the ever-larger, ever-uglier fortified SUVs that are choking our cities.

So why is Critical Mass still necessary?

100 deaths and 4,000 serious injuries from road traffic accidents in 2022 is why. Air pollution levels that lead to thousands of hospital admissions for asthma and thousands of premature deaths per year is why. Nine-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is why.

But it’s not just a matter of protesting the worst things about our cities. It’s because — whether you have any interest in cycling or not — we all could be living in happier, healthier, more sociable cities, and this is the utopian glimpse into the future that Critical Mass offers to everyone. One old CM flyer dangles exactly this possibility to non-cyclist bystanders — to the pedestrians watching on, laughing and taking photos, as the two-wheeled carnival transforms the urban landscape:

“As we pass by, you have a few moments to ponder the pleasantness of your surroundings without the usual noise, stress, danger and frustration which bombard your senses. It could be this pleasant all the time.”

I return to that line I quoted at the start, “we run the streets today”. It’s a cheering sentiment, but there’s something poignant about it too — because today is the only day we get to run the streets. Today is the exception. It’s the same with carnivals, with protests, with holidays, with snow days, with the London Marathon, even — these are the exceptions to the rule, they are thrilling for the very reason that the everyday (rat-)run of things, everyday life under capitalism, has been turned upside down. All I’m saying is: maybe we should do this a little more often.

Just caught up on this and really enjoyed it!

Will look out for the next Critical Mass event in London to join. What I find interesting is the disconnect between the huge anti-ULEZ noise in the media and online and the fact that people keep voting for safer, cleaner streets. The quiet majority rule!