How to lose your home

The fastest-eroding coastline in Europe and Yorkshire's lost pirate Atlantis

Like all cool people with their priorities in order, I am easily taken in by the words “medieval pirate Atlantis”. This was the approximate description in a quirky news story 18 months or so ago, about a man hunting for the sunken village of Ravenser Odd (what a name!), a place that emerged on a sandbank on the East Yorkshire coast for barely a century and a half in the 13th and 14th centuries, before once again disappearing beneath the waves. That man was Prof Dan Parsons, he had access to a submarine with high-tech, sea-floor scanning equipment, and he was hoping to find the remnants of Ravenser Odd. Would there be buried treasure, pirate ghosts, possibly some kind of curse? In the absence of evidence to the contrary, it seemed safest to assume the answer was yes.

I got hold of Dan Parsons, who turned out not to be a time-travelling pirate with a score to settle, but a very affable climate scientist, looking for fresh ways to engage the public with stories about the loss of towns, villages and homes in the climate emergency. From wildfires to flooding and — in the local case in East Yorkshire — drastic coastal erosion, we need to be able to think outside the ‘extreme present’, and beyond the political class’s ruinous short-termism that threatens to kill us all and the only planet we have. Not to be melodramatic or anything.

The more I read about the Holderness coast of East Yorkshire, the more I realised that there was an even more gripping story than that of the medieval pirates (though I’m pleased to say Robert Rotenherying and Hugh le Flekmaker were real people, as you will discover below). So I travelled via Hull on the train and then a very windy bus through flat, sparsely-populated Holderness to the off-season coastal resort of Withernsea; where the lighthouse is 500m inland for safety reasons, and the pier was washed away in fierce storms only 16 years after it opened.

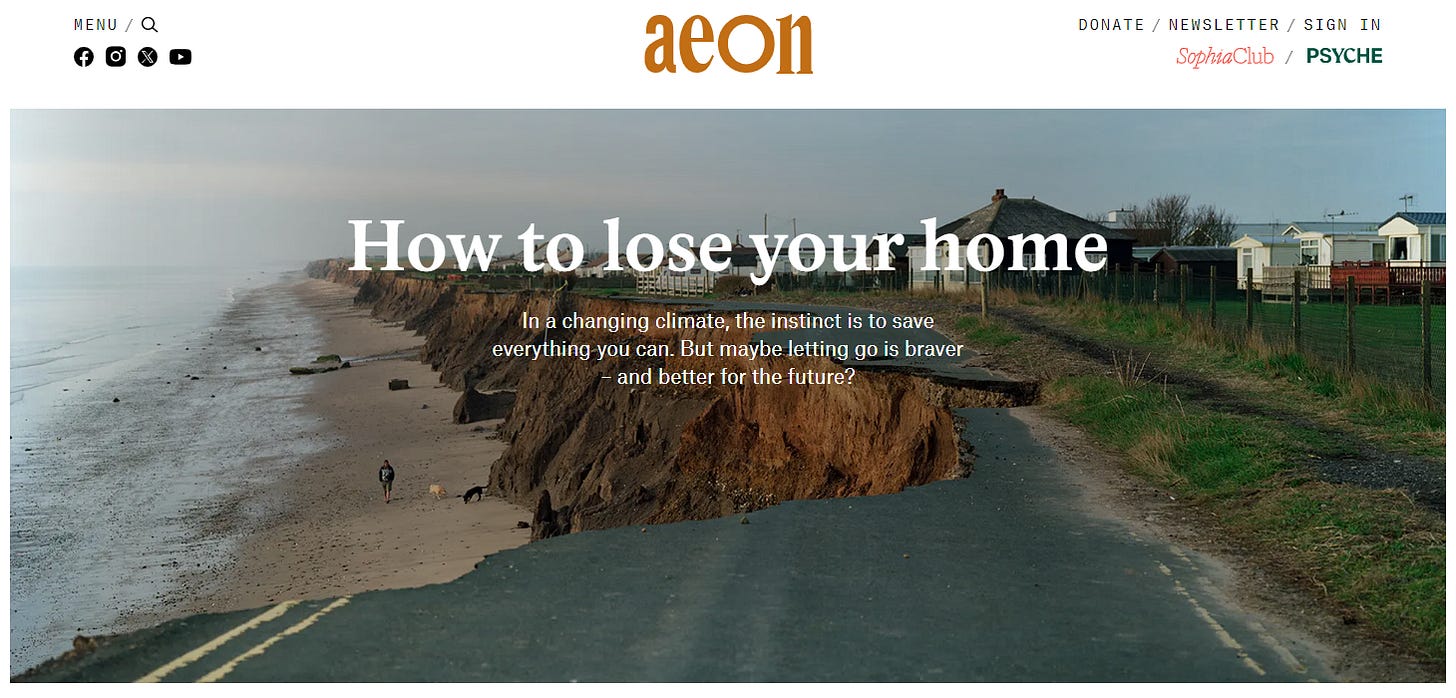

This 61km stretch of coast is retreating at a rate of 2 metres a year on average, making it the fastest-eroding coastline in Europe — in its most vulnerable sections, parts of Holderness’s soft clay cliff have crumbled a staggering 15 metres in a single year. Fifteen metres! In a year! How do you live with this kind of precarity, and what are the local authorities doing, with stretched resources, to help people living on the literal cliff-edge? What gripped me above all is the fact that this is not a new phenomenon in Holderness, but a process that precedes the climate emergency by hundreds of years.

Everywhere I went, there were bits of salvaged rubble, physical testaments to lost villages, long since drowned and now hundreds of metres, or even miles, out into the icy North Sea. In the age of climate emergency and the necessity of ‘managed retreat’ from the fire, floods and erosion, what can we learn from Holderness? Can we learn to embrace our own impermanence?

The full essay is here to read on Aeon magazine, no paywall or anything. It took weeks, as well as some wonderfully deep and thoughtful editing from the brilliant Marina Benjamin, so I’d love if you made a cup of tea and gave it a read.

This is a video of East Riding’s Coastal Change Manager Richard Jackson showing me how much has disappeared from one part of the coast since the 1960s. It’s pretty wild.

*****

And finally, a quick reminder that I published a new book in October, MULTITUDES: How Crowds Made the Modern World, that I’m very proud of it, and that you could plausibly buy it as a Christmas gift — or better, for yourself — it’s short and zingy and I think will make you think about crowds, public space, collective joy, carnivals, riots and fascism in surprising ways. You can buy it with a discount from Hive here and support independent bookshops in the process.

In addition to the 400 podcasts I’ve done, by way of introduction to Multitudes, and a hilarious, wildly disingenuous screed across several pages of the New Yorker by someone who does not appear to have read more than the first three chapters, there was a wonderful review in the New Statesman last week by Sophie McBain, which you can read here. Very pleasing to be described as having a “deeply humane perspective”, what more could you ask for really?

Nothing to do with pirates! Ravenser emerged from the sea to become a thriving port with its own charter and local government. Mooring fees helped maintain the port but horrifically high seas put an end to it in the Grote Mandrenke, the great drowning of men that destroyed much of the Netherlands in 1362.