One of the antisocial delights of writing a book is that you are destined to disappear into a series of darkened caves illuminated only by your own research, such that you inevitably end up somewhat manic-obsessive by journey’s end. Monomania being an occupational hazard, it’s good to have something that isn’t the book to obsess over when you clock off. During the short days and long nights of winter 2023, when I was finishing Multitudes, that something was Dublin’s finest anarcho-doom-folk quartet Lankum. I would shut the laptop window containing my manuscript, pour myself a big drink, open YouTube, and watch Lankum live videos until it was time for bed, lost in the giddy trad-punk energy of fiddle-led standards, polkas and reels like Bear Creek, Lucy Campbell’s and Angeline the Baker, or the hypnotically slow harmonies of gypsy love song Rosie Reilly.

I’ll post a playlist of my favourites below — but there’s one track in particular where the obsession just will not leave me. That song is Hunting The Wren, an original composition written by Lankum’s Ian Lynch in 2019, after a song-writing challenge between him and (also brilliant) fellow Irish singer-songwriter Lisa O’Neill. Lynch gave O’Neill would-be Mussolini-assailant Violet Gibson as a subject, and she in turn gave Lynch the Wrens of the Curragh.

Hunting the Wren is not an easy listen. It’s a seven-minute long march of the dead, at once hypnotically beautiful and laden with grief and tragedy. Lynch’s poignant and economical lyrics and Radie Peat’s breathtaking lead vocals are in large part responsible for conveying that tragedy, but the arrangement tells the same story. Most chilling is the sinister rattle of percussion, sparse but persistent, reminiscent of a chain gang trying to force a rhythm out of anything that might alleviate their miserable fate. There is the insistent twang of a plucked violin, the ominous thud of a bass drum, and on top of it, a blanket of unease, rather than a ‘tune’, per se: a low hum of evil droning out from synth, trombone and accordion. This spartan template gives Radie’s vocals the space to soar to spectacular heights.

But let’s get to Hunting The Wren’s subject matter. The lyrics delicately weave together Irish folk traditions and mythology about the wren (the bird) with a gut-punching piece of little-known human history.

The Wrens of the Currah were a community of 60-100 mostly young women living in Ireland in the second half of the 19th century — women who had been violently cast out by society, left destitute, homeless and starving, many orphaned by the inflicted horrors of the famine. In the face of complete abjection they formed a collective of outcasts, sharing food, resources and childcare, and living, in the summer at least, “on the wide open plains” of Kildare, working as sex workers for soldiers at the British Army’s nearby Curragh Camp. The Wrens were so-called because they slept in hollows in the ground, amongst furze and gorse bushes, like the nests of the birds of the same name. Local historian Con Costello describes the women’s ‘nests’: “Located in a clump of furze… each nest consisted of a shelter measuring some 9’x7’ and 4’2” high, made of sods and gorse. With a low door, and no window or chimney, and with an earthen floor, the ‘nest’ had for furniture a shelf to hold a teapot, crockery, a candle, and a box in which the women kept their few possessions.”

They were treated with the contempt and violence you would expect by the British soldiers, but not only by them. There are accounts of priests whipping the women of the Curragh, stoning them and beating them out of the nearby towns, and another account of a priest forcibly cutting a woman’s hair “close to the head”, in order to mark her, and make it clear she was not accepted in polite Christian society. It is all agonisingly sad and enraging.

“Attacked in the village, spat on in town / They come from all over, to hunt the wren on the wide open ground.”

I am no expert in the Curragh Wrens, and have just started reading what I could find online. There are a smattering of accounts, including these 1867 reports by journalist James Greenwood (click ‘next chapter’ for more), and a good summary in this Irish Times piece from 2001, where the writer visits one of the wrens’ former ‘nests’ on the Kildaire plains. I also read this contemporary account, from a magazine article by a budding journalist called, um, Charles Dickens:

There are, in certain parts of Ireland and especially upon the Curragh of Kildare, hundreds of women, many of them brought up respectably, a few perhaps luxuriously, now living day after day, week after week, and month after month, in a state of solid heavy wretchedness, that no mere act of imagination can conceive. Exposed to sun and frost, to rain and snow, to the tempestuous east winds, and the bitter blast of the north, whether it be June or January, they live in the open air, with no covering but the wide vault of heaven, with so little clothing that even the blanket sent down out of heaven in a heavy fall of snow is eagerly welcomed by these miserable outcasts…

If one of these poor wretches were to ask but for a drop of water to her parched lips, or a crust of bread to keep her from starving, Christians would refuse it; were she dying in a ditch, they would not go near to speak to her of human sympathy, and of Christian hope in her last moments. Yet, their priests preach peace on earth, good will among men, while almost in the same breath they denounce from their altars intolerant persecution against those who have, in many cases, been more sinned against than sinning. This is not a thing of yesterday.

‘Stoning the Desolate’, Charles Dickens, All the Year Round, No 292 (1864)

As an aside, the teenage atheist in me that bubbles to the surface now and then can’t help but observe: this is 1864 in England, as church attendance and god-fearin’ is collapsing on this side of the Irish Sea, particularly among the rapidly amassing urban working-classes of the big cities — and it is envigorating to see Dickens very much not holding back. It feels like a moment of heathen revelation, a speaking of what had too long been unsayable about the priesthood’s grim amorality and hypocrisy.

The wren itself, meanwhile, is subject of a famous Irish folk song in its own right. Wren Day, St Stephen’s Day, is 26 December, when “She soon is run down / Her body paraded / On a staff through the town” — this refers to the traditional mock-hunt of a wren, where an effigy of the bird is held up on a pole by ‘wrenboys’. The wren is the king of all birds in various strands of northern European folklore. It holds this title thanks to a story whereby the birds compete to elect a king, based on who can fly the highest; the small and feeble wren hides in the eagle’s wings, hitches a ride, and soares higher than the eagle.

In Lankum’s telling, the wren is bedraggled, and unlovely, “with two broken wings / and feathers so brown” — but in amongst all the supplication, persecution and misery it has suffered, it is still capable of an implausible redemption:

“The wren is a small bird, how pretty she sings / She bested the eagle, when she hid in its wings”

I find myself rewinding to hear Radie sing this line over and over — it’s right near the beginning — borne of a kind of desperation that accumulates by the end of the song: please tell me there was some kind of salvation? Some way out?

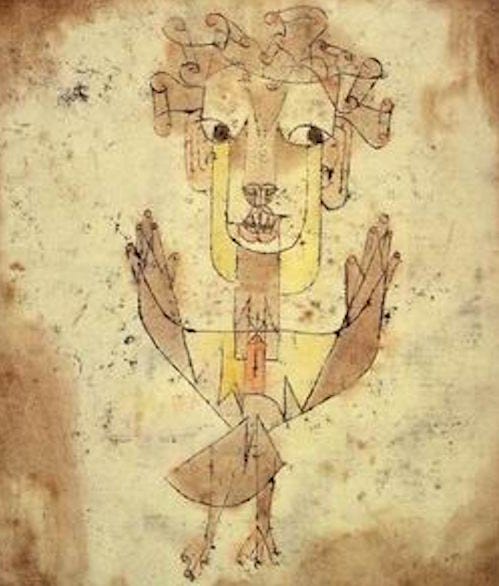

Stay with me for the final piece of monomania, as we continue to awaken the dead. I have become obsessed with Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History recently — a scrapbook of 20 fragments, written by Benjamin in a moment of great danger, in the winter of 1939, as the Nazis advanced towards him in Paris. He would die by suicide the following September, still on the run from what he called the ‘Antichrist’ (fascism). Benjamin’s Theses were not intended for publication, but as a series of intellectual prompts and guides to himself. Decoding them is a delightfully endless task, because they are so richly ambiguous that there is no ‘right answer’ to their meaning. I’ve begun to use them as a kind of intellectual master-key, when writing about the Attlee goverment’s secret deportation of Chinese seamen in 1946, or to try and understand why proper binmen memes are so popular with boomers on Facebook — or indeed, why Hunting the Wren hits so fucking hard.

Benjamin’s theses urge us to rescue the downtrodden, oppressed and forgotten — the human beings treated like rubble, across the long and barbaric history of civilisation — and to join the Angel of history in his mission to “awaken the dead and make whole that which has been smashed”. History is written by the victors, and it’s about time we did something about that.

Because the telling of history is too often sanitised, simplified or distorted beyond all recognition by a ruling class with a vested interest in presenting a neat narrative of linear progress. Even histories of the Suffragettes or the US civil rights movement have become cosy myths of peaceful supplication — it’s there in books called things like Seven Badass Women Who Asked Very Nicely For Change; no violent misogyny, arson or broken windows on show. TV comedians bring us best-selling books about Kings, Tory toffs present the leading history podcasts.

But we have the power to address this, Benjamin writes: in fact, our greatest hope of emancipation will come not from utopian dreams of liberated grandchildren, but from saving our oppressed ancestors from obscurity, and bringing them out into the light.

All of which is to say: Lankum are absolutely doing Benjamin’s work here, bringing the story of the Curragh Wrens out into the light, and doing so in the way only great art can. One review I read of The Livelong Day — the studio album which first gave us Hunting the Wren — was headlined “Lankum Won’t Let Ireland Forget”.

Here’s that Lankum sessions/live playlist, and relatedly here’s the Mary Wallopers feature I wrote for The Observer in July, if you missed it. Not a very cheerful post I’m afraid. But! I’ve been listening to Hannah Diamond and Tiwa Savage cycling to and from work this week, to alleviate it being grey all day and then dark at 3 sodding 45 pm, I can recommend doing the same. Also, a Lumie lightbox (not spon). And there’s a Christmas Cursed Objects out now, that’s much more fun. The Christmas singles pop quiz is here on the Cursed Objects Patreon as a bonus mini-episode, and over the holidays there’ll also be another bonus Patreon episode recorded ~on location~ in a plausibly haunted seaside hotel.

Have a Merry Christmas, a Happy Hanukkah, a fruitful Wren Day, a banging New Year’s Eve — and don’t forget.

Amazing stuff - on my way to see them at Crystal Palace tonight! No one else comes close 👊

Fascinating read, thank you! I had never heard of the wrens, another dark corner of Ireland's long history of misogyny!